Real Time Response — Old Technology that Continues to Inspire

“Real Time Response Measurement” (RTR) is an instrument-based research method whose origins date back to the 1930s. Despite its age, it is anything but outdated. With this method, media content can be evaluated to the second and simultaneously upon reception. This is done by respondents in focus groups or larger Hall-Tests.

Paul Felix Lazarsfeld is known to many readers for his sociographic study “Die Arbeitslosen von Marienthal” (1933), in which he examined the sociological changes following the closure of a factory in a small Austrian town where most of the inhabitants previously worked in the same factory and from one day to the next all became unemployed.

At least as famous is his ground-breaking study “The People’s Choice”, which was innovative for communication research. The study interviewed voters of an Ohio county about the upcoming presidential election in 1940 and examined the emergence of personal voting decisions. He thus founded the communication model of the “two step flow”, according to which the media first reach “opinion leaders”, who then filtered and weighted the original information and pass it on to their “peer group”. Even though the model as a whole has lost importance due to the impact of television as a mass medium, the term “opinion leader” still plays an important role in empirical research.

Somewhat less well known is the fact that the Austrian Lazarsfeld originally studied mathematics and taught this subject as a high school teacher in Vienna in the 1920s, before teaching at the Psychological Institute of the University of Vienna in the early 1930s. These disciplines were probably also decisive for his technical developments, which he pursued further after his emigration to the USA in 1933. As director of the “Office of Radio Research” at Princeton University, he developed the “Stanton-Lazarsfeld Program Analyzer” together with Frank Stanton, later president of CBS. With the help of an apparatus, test persons could tell how much they liked what they heard while listening to a “radio drama” (early form of soap opera). At any moment, pressing a green button could give a positive rating, or pressing a red button a negative rating. Each test person received a corresponding handheld device, which then emitted electrical impulses, which the Program Analyzer, affectionately called “Little Annie” by the inventors, drew on a kind of roller plotter as a long line. Comparable to an ECG graphic, the degree of the likes or dislikes could be displayed on the time axis, so that each scene of the drama could be analysed exactly afterwards.

This “Real Time Response” method (which some also call the “Continous Response” method) became more and more important in the USA. While radio broadcasts were the main focus of research at the beginning, television broadcasts became increasingly important later on. The handsets for the assessment were further developed and were given a knob that could no longer be used to record only dichotomous answers such as “yes/no”, etc. The new system was also used to make the assessment of the TV programmes more precise. With the handset now known as the “dial”, a ratio scale from 0 to 100 could be used for a quasi-stepless query, which made it possible to fine-tune the rating for the measurement over time. With the introduction of wireless dials, which continuously sent their measured values by radio to the base located in the room, the usability of the test persons increased, who could now position themselves more freely and more relaxed. The test setup became much simpler and faster as there was no need to wire the devices or glue the tripping cables.

Input device of an RTR system (“Dial”) („Dial“)

An exciting field became for example the “Presidential Debates”, with which the candidates for the White House debated in front of the camera. Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Barack Obama and many more: They and their opponents all had to face the tough jury of research teams, who sat in front of the television simultaneously with participants from larger focus groups, evaluating moment by moment, word by word and argument by argument. It is not only what is explicitly said that is evaluated. Non-verbal communication, gestures and facial expressions also play their part in the evaluation of the test persons. However, this lack of separation between cognitive and affective influences on the evaluation is not necessarily a disadvantage. According to the American principle of “keep it simple”, exactly what is important in the election decision is mixed: a mixture of head and gut feeling, knowledge of concrete election statements and sympathy or antipathy towards the candidates.

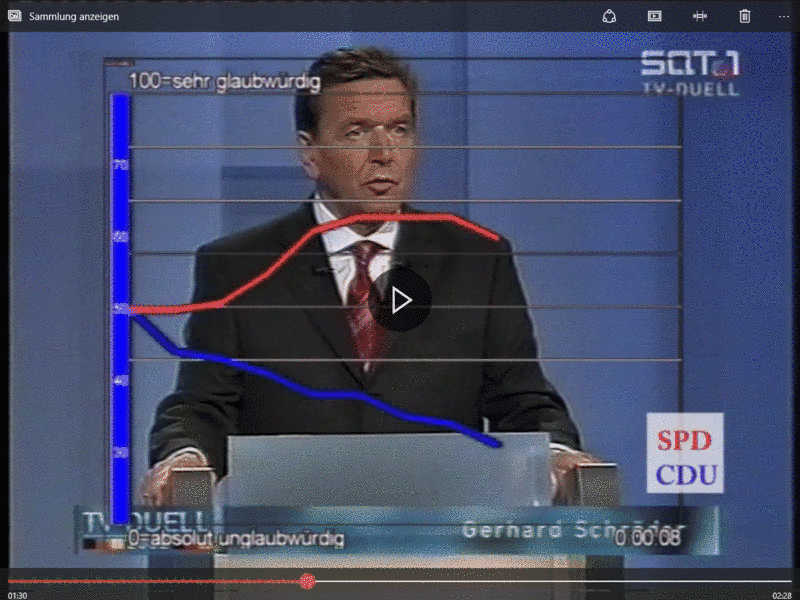

RTR measurement of the TV Debate of 2002

TV debates are also attributed a major role in the outcome of elections because undecided voters often decide in favour of a party only before the ballot box, when there is no time left for weighing up factual arguments. Many then decide in favour of the party they believe will win the election because they want to be on the winning side. This “band wagon effect” was also a result of Lazarsfeld’s “The People’s Choice” study.

As the author’s experience shows, the RTR method can be used to analyse very different objects of investigation very well in focus groups or in larger auditoriums. In general, all audio-visual and auditory media can be used, for example any kind of television format, commercials, program sections or entire music catalogues from radio stations to feature films in the cinema. Live events such as musicals or party conferences can also be studied, as the wireless devices with radio transmission do not require special test rooms.

TV debates are also attributed a major role in the outcome of elections because undecided voters often decide in favour of a party only before the ballot box, when there is no time left for weighing up factual arguments. Many then decide in favour of the party they believe will win the election because they want to be on the winning side. This “band wagon effect” was also a result of Lazarsfeld’s “The People’s Choice” study.

As the author’s experience shows, the RTR method can be used to analyse very different objects of investigation very well in focus groups or in larger auditoriums. In general, all audio-visual and auditory media can be used, for example any kind of television format, commercials, program sections or entire music catalogues from radio stations to feature films in the cinema. Live events such as musicals or party conferences can also be studied, as the wireless devices with radio transmission do not require special test rooms.

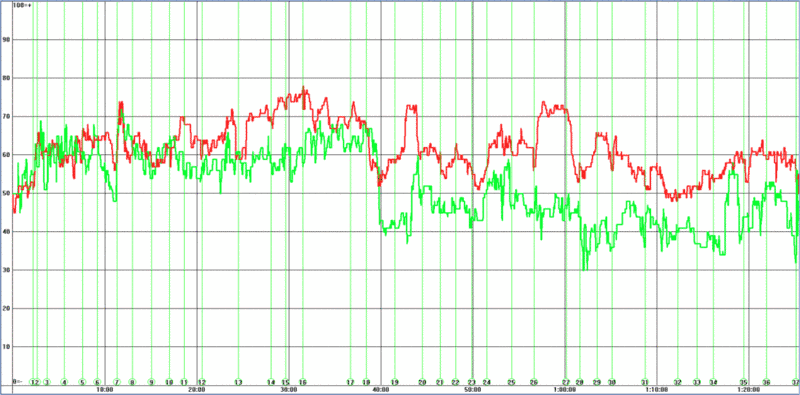

Evaluation of an arthouse film by persons with high (red) and low (green) affinity for the format

What is appealing about the technology is not only being able to view the likes and dislikes of every second of a media content, but also to see the ascending and descending evaluation curve simultaneously, i.e. during the reception of the media content by the test persons. In the focus group, for example, you can hear the laughter or see the serious faces while the test persons put their dials in a negative position, which helps the interpretation.

In August 2002, for the first time in Germany, there were speech duels between Chancellor candidates on German television. After Helmut Kohl had always rejected this, Gerhard Schröder was the first to enter the ring of TV journalists. While Schröder was simultaneously duelling verbally on Sat.1 and RTL with his challenger Edmund Stoiber, 100 test subjects, selected according to party percentage and socio-demographic characteristics, watched the live broadcast in a Berlin hotel hall on a big screen at the same time and evaluated the events with their dial. The evaluation curve revealed to the second which arguments Schröder was ahead of and where Stoiber was able to score. The breakdown by party affiliations can reveal interesting dissonances, for example if the agreement of the opposing camp is greater than one’s own.

Even though this measurement very clearly depicted Schröder’s later election victory, it is of course not a forecasting instrument. Due to the fact that the number of cases is usually limited to a few hundred participants, but also due to the lack of a representative sampling approach, this is a qualitative research procedure whose results cannot be extrapolated. Rather, the benefit of the procedure lies in the qualitative analysis of the media impact. In the above example, how are political messages evaluated in terms of content and substance? To what extent can the type of presentation by the speaker, his or her rhetoric, gestures and facial expressions, his or her credibility and the competence assigned to the topic be convincing? Knowing the influence of these factors on their media impact, some presidential candidates in the USA are said to have been prepared for the TV debates with the help of RTR.

It is very similar to politician debates with commercials, which can also be examined for their communication performance via RTR. Here alternative motives are tested against each other or also Storyboards are examined, before they are produced expensively. In some cases, a combination of RTR with physiological methods can also be used to get closer to the unconscious (advertising) effect. In my opinion, however, this is not recommended in general, but rather for basic studies that justify high effort for small samples. The affective components can also be recorded quite well with RTR if the method is operationalized correctly.

However, it is precisely ignorance of correct operationalisation that sometimes leads to methodological scepticism, which is often not justified. For example, it is very important how the endpoints of the scale are named in the RTR measurement. A scale from “I like it very much” to “I don’t like it at all”, for example, when evaluating a drama, it makes no sense at all. A violent scene can be very important for the narrative and also for the audience. But hardly any normal person would answer with “I like”. Facebook also has this problem with its thumb pointing upwards and being used sometimes for approval and sometimes for the opposite. Here you rather need a scale for the involvement of the audience, that meets the different needs and expectations of the movie usage like entertainment, fun, excitement among other things much better.

There is also scepticism regarding the length of the format to be examined, the longer the test, the more likely it is that the test subjects will apathetically freeze and forget the evaluation. If the test persons are properly instructed in a warm-up, they quickly learn to use the dial very intuitively and almost unconsciously, without any significant signs of tiredness. This can be shown both by looking at the high volatility of the individual evaluation curves and with a high test-retest reliability between the evaluation of a content at the beginning of the test and again the same content at the end of the test.

As the RTR curve of a feature film from the arthouse area shows, the RTR curve can not only be observed live, but can also be printed ex-post for any subgroups, whereby the scenes of interest or striking twists in the plot can also be well displayed and interpreted.

Despite the depth of information that a well-planned RTR can offer, it should be integrated into subsequent focus groups, at least for AV media, in order to be able to assess the dimensions that are only possible following the film.

This article was published as a dossier in marktforschung.de in December 2015.

von

von